| Swasth Nari, Sashakt Parivar Abhiyaan: A Call to Health beyond Survival | | |  Dr Manorama Bakshi Dr Manorama Bakshi

India has been working on women’s and children’s health for over a decade now. It has not been in vain. Maternal deaths have dropped. More babies are born safely in hospitals. Vaccines reach even the remotest corners. These are victories we should not forget. But survival, though essential, is only the first step. A society cannot be truly healthy if its women remain anaemic, its children stunted, and its adolescents unprepared for the demands of modern life.

On 17 September 2025, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the Swasth Nari, Sashakt Parivar Abhiyaan. The campaign promises 100,000 health camps, stretching from Ayushman Arogya Mandirs to district hospitals, combining nutrition counselling, anaemia screening, menstrual health education, and even specialist services for tuberculosis, sickle cell, and mental health. The two ministries—Health and Family Welfare, and Women & Child Development—are working hand in hand. On paper, it looks ambitious. On the ground, it could mean something even bigger: the possibility of shifting our national conversation from merely saving lives to ensuring lives worth living.

A Decade of Learning

India’s health journey has not lacked intent. The RMNCH+A strategy of 2013 brought focus to high-priority districts. Anaemia Mukt Bharat in 2018 tried to crack the iron-deficiency puzzle with its six-by-six plan. The School Health and Wellness Programme (2018–20) planted the seeds of adolescent health education.

Yet, the NFHS-5 data (2019–21) tell a sobering truth:

• 67% of young children are still anaemic.

• 57% of women of reproductive age remain anaemic.

• 35% of children under five are stunted.

These numbers aren’t just statistics. They are silent barriers, holding back the very society we wish to build.

The Cost of Inaction

What does it mean when half our children grow up anaemic or stunted? It means lost potential—smaller bodies, slower minds, and weaker resistance to disease. It means a workforce that is less productive, and a generation that cannot compete in the global economy.

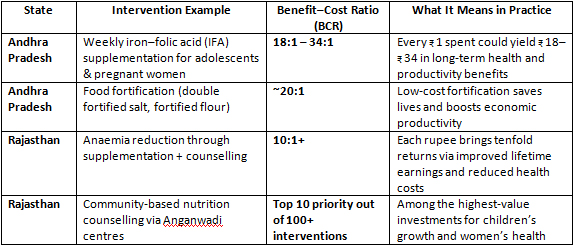

The India Consensus Project, a collaboration between Tata Trusts and the Copenhagen Consensus Center, put numbers to this reality. Working in Andhra Pradesh and Rajasthan, economists tested more than 100 interventions and asked: which ones give India the biggest return for each rupee spent? The answer was clear: tackling anaemia and malnutrition is one of the best investments this country can make.

Cost–Benefit Findings from the India Consensus Project

Source: India Consensus Project (Tata Trusts & Copenhagen Consensus Center)

In plain terms: every rupee we put into nutrition today could return ten, twenty, even thirty rupees tomorrow in healthier, smarter, more productive citizens. Ignoring malnutrition is like burning money we don’t see.

A Healthier Society, Not Just Healthier Numbers

Good health does not begin in a clinic. It begins at home. It begins when families choose to speak about nutrition at the dinner table, when parents make sure their children eat iron-rich foods, when mothers ask for haemoglobin tests at health camps, and when fathers and daughters alike talk about menstrual health without shame. The first defence against anaemia and stunting is not a government office—it is the daily choices made inside our homes.

But families do not walk this path alone. Across India, an invisible army of women stands beside them. ASHA workers go door to door, checking on expectant mothers, distributing iron tablets, persuading families to vaccinate, and sometimes simply offering a listening ear. Auxiliary Nurse Midwives (ANMs) at sub-centres provide antenatal check-ups, safe deliveries, and referrals when danger signs appear. These women are the quiet bridge between households and the health system, often doing their work in the toughest conditions.

Around them, Anganwadi workers ensure young children are weighed, counsel mothers on feeding practices, and demonstrate nutritious recipes. Together, these front-line workers are the backbone of the Swasth Nari, Sashakt Parivar Abhiyaan. The campaign gives them new tools, but their mission has always been the same: to transform not just health statistics, but everyday lives.

The early battles—reducing maternal mortality, expanding immunisation, ensuring institutional deliveries—are being won because families trusted these women and these women refused to give up. The new battles are harder. They demand that we change diets, break habits, and dismantle the silent disadvantages passed down from one generation to the next. No pill or target alone can achieve this. It requires social change, and that begins with families—but it succeeds only when supported by ASHAs, ANMs, Anganwadi workers, and the wider community.

Conclusion

The Swasth Nari, Sashakt Parivar Abhiyaan is both a continuation and a challenge. It reminds us that while India has moved far, the road ahead is longer still. Freedom from anaemia and stunting is not a luxury—it is the foundation of human dignity and national strength.

Economists from the India Consensus Project have shown in plain numbers what families know in their hearts: every rupee invested in nutrition today can return ten, twenty, even thirty rupees tomorrow in the form of healthier, more capable citizens. Ignoring malnutrition is not saving money—it is quietly losing it.

We have been working at this for decades. We have seen lives saved, mothers survive childbirth, and children vaccinated. But until every woman is strong in body and mind, until every child grows without hidden hunger, our society will still carry a silent burden.

This campaign, if embraced with seriousness by both government and citizens, could mark the moment when India moves beyond reducing deaths to nurturing fuller, stronger lives.

Dr. Manorama Bakshi is the Director & Head of Healthcare & Advocacy at Consocia Advisory, Founder of the Triloki Raj Foundation, senior visiting Fellow IMPRI. A public health and policy strategist with two decades of experience working across government, multilateral agencies, and grassroots movements. |

|